Ustad Mansur – A Wonder Of His Age

BOOKMARK

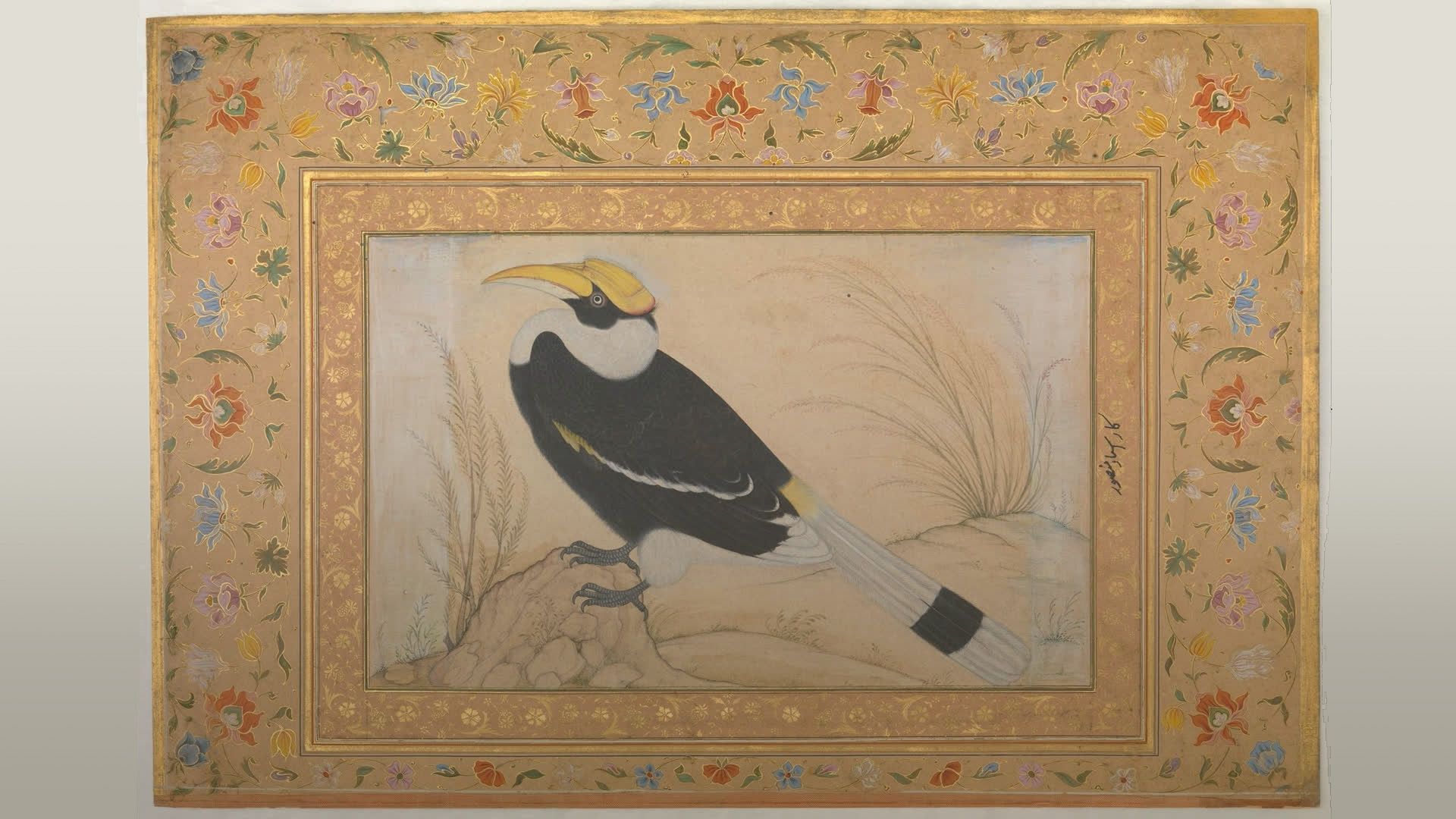

Unlike a Rembrandt, a Michelangelo or a Van Gogh, the great Indian painters of the medieval period have been relatively nameless and faceless. The great Indian works of art are known by their patrons. Only a few famous painters like Nainsukh, Basawan and Mansur, are known and that too in art history circles. Art history researcher, Manoj Dani takes a look a the works of Mughal Painter Ustad Mansur, whose realistic paintings of flora and fauna so impressed Emepror Jahangir and continue to impress art lovers even today.

July 1618 – The Jahangirnama

‘[Abul Hasan] is truly a rarity of his age. So is Ustad Mansur, the painter who enjoys the title of Nadirul’Asr [Rarity or Wonder of the Age] In painting, he is unique in his time. During my father’s reign and mine, there has been and is no one who could be mentioned along with these two.’

The fate of one of India’s greatest painters, Ustad Mansur, was closely tied to the great patron of the arts of his time – Mughal emperor Jahangir (1569-1627 CE). Mansur had supported Jahangir quite early when Jahangir had rebelled against his father, Emperor Akbar (1542-1605 CE). This is evident from his dated and signed painting depicting Jahangir as ‘surat badshah’ even when Akbar was alive and Jahangir was still a rebel Shahzada Salim in 1600-1601 CE!

It is unfortunate that we know almost nothing about Mansur’s life beyond his work in the Mughal atelier. Mansur began his career at the Mughal Court in 1589, and one can find his work in the paintings of Akbarnama, commissioned by Emperor Akbar. The Mughal atelier, established by Emperor Humayun (1508-1556), reached the height of its glory under Emperor Akbar, who commissioned some of the most spectacular works such as Hamzanama, Akbarnama, Anwar-i-Sohaili and even translations of the Ramayana and Mahabharata.

But working under Akbar while Mansur was not a master painter or ustad, one can see the superb borders and illuminations he had put together for other major artists’ works. Mansur’s personal contributions seem to have been a precise, warmly observant description of the subject and a tightly controlled, obedient technique that was more colored drawing than painting.

Mansur shot into the limelight during Jahangir’s reign. As mentioned earlier, Mansur was a supporter of Prince Salim when he had rebelled against his father, and Mansur’s status rose when the rebel Prince became Emperor Jahangir, on the death of his father in 1605 CE.

From grand scenes and fantasy tales depicting aspects of Akbar’s life, Mughal painting took a very different turn towards realism under him. Emperor Jahangir was a lover of plants and animals and in his autobiography Tuzk-i Jahangiri, he writes firsthand about what motivated him to commission these paintings. Jahangir writes about the curiosities from Portuguese-ruled Goa:

‘On the 16th Farwardeen, Muqarrab Khan came from the fort of Cambay and had the honour of waiting on me I had ordered him, on account of certain business, to go to the port of Goa and buy for the private use of the government certain rarities procurable there. According to orders, he went with diligence to Goa, and remaining there for some time, took at the price the Franks asked for them the rarities he met with at that port, without looking at the face of the money at all (i.e. regardless of cost). When he returned from the aforesaid port to the Court, he produced before me one by one the things and rarities he had brought. Among these were some animals that were very strange and wonderful, such as I had never seen, and up to this time no one had known their names.

Although King Babar has described in his memoirs the appearance and shapes of several animals, he had never ordered the painters to make pictures of them. As these animals appeared to me to be very strange, I both described them and ordered that painters should draw them in the Jahangirnama so that the amazement that arose from hearing of them might be increased. One of these animals in body is larger than a peahen and smaller than a peacock. When it is in heat and displays itself, it spreads out its feathers like the peacock and dances about. Its beak and legs are like those of a cock. Its head and neck and the part under the throat are every minute of a different color like a chameleon. When it is in heat it is quite red - one might say it had adorned itself with red coral - and after a while it becomes white in the same places and looks like cotton. It sometimes looks of a turquoise color. Like a chameleon, it constantly changes color.’

In the above lines, Jahangir is describing a turkey bird that the Portuguese had brought from South America. The painting of the turkey done by Ustad Mansur for Jahangir has survived and one can see how the description given by Jahangir in his autobiography matches the artwork.

Mansur’s most brilliant portrait was his contributions to the Muraqqa-I Gulshan, the great album that Jahangir started assembling while he was still a prince.

Mansur was able to capture not only the physical texture of living breathing birds and animals, but also a sense of their inherent nature.

Jahangir noted in his memoirs that the chameleon ‘constantly changes colours’, a peculiarity which is perhaps hinted at in this painting of the small, slow-moving reptile with the turquoise-green tones of its skin used again in the leaves of the branch where they merge with yellowing hues. In addition to his acute powers of observation, Mansur is celebrated for his extraordinary handling of paint, here demonstrated in particular by the tiny impasto dots simulating the surface of the chameleon’s skin. On very close inspection, a gold crease is visible, creating a glint in the reptile’s eye.

Under 31 October 1619, in Jahangirnama, we find Mansur again.

‘The ruler of Iran had recently sent a falcon of good colour with Piri Beg, the chief falconer. He had given another to Khan-e Alam, who had sent his falcon with the royal falcon destined for the Court. Khan-e Alam’s died along the way, and the royal falcon was clawed by a cat through the falconer’s negligence. Although it was delivered alive, it didn’t live more than a week before dying. What can I write of the beauty of the bird’s color? It had black markings, and every feather on its wings, back and sides was extremely beautiful. Since it was rather unusual, I ordered Ustad Mansur, the painter, to draw its likeness to be kept.’

Today we find the painting of the falcon in the British Museum.

One of Mansur’s paintings – the Siberian Crane – is a valuable record of natural history as this bird is no longer seen in India today. The painting, somewhat damaged, is signed by Mansur at the bottom (‘Amal Ustad Mansur’)

Towards the end of Jahangir’s reign, we see a superbly depicted zebra by Mansur with a note in Jahangir’s own handwriting.

‘A mule [astari] the Turks [rumiyan] in the company of Mir Ja'far brought from Ethiopia [Habasha]. Its likeness was drawn by Nadiru'l-'asri [Wonder of the Age] Master Mansur. Year 1030, [regnal or Julus] year 16.’

After Jahangir’s death in 1627 CE, we no longer find any works of Ustad Mansur. All curiosities of nature in paintings were replaced by the hierarchical, grand paintings showing off the architecture and wealth of his successor Shah Jahan. It is unknown how Ustad Mansur died – all that survives today is his great works scattered across museums all over the world, where one can enjoy and marvel at his works – he was truly a ‘wonder of his age’.

– AUTHOR

Manoj Dani is a independent researcher of art history based in California and is currently working on classifying the art treasures of BISM, Pune.