Luis de Menezes Braganza: Goa’s Crusader for Freedom

BOOKMARK

It is an irony that one of Goa’s greatest intellectuals, who sparked off a movement against colonial Portuguese rule, was named after the reigning Portuguese monarch King Luis I. Born in 1878, Luis de Menezes Braganza, had everything going for him - great wealth, vast estates, the largest mansion in Goa and a family name that reigned over Goan high society. But Luis, chose to sacrifice it all for the cause of Goa’s freedom from colonial rule.

The 17th century ‘Braganza House’ in Chandor, in South Goa, is famous for its opulence and antiquity. Considered to be the largest private house in Goa, it boasts of two ballrooms, a huge banquet hall and an enviable collection of art and antiques including a set of gilded chairs gifted to the family by the King of Portugal in 1848. It was in this very house, amid opulent luxury, that Luis de Menezes Braganza grew up. Born on 15th January 1878 in Chandor, his mother belonged to the distinguished Braganza family of the same village. Originally a Hindu Desai family the Braganza’s had converted to Christianity after the Jesuit missionaries came to Goa in the mid-16th century. His maternal grandfather Francis Xavier Braganza had no son and so he appointed his eldest daughter’s son i.e. Luis as his heir with the condition that he continue using the family name. From the 17th century right till 1961, the Braganzas were one of the largest land owners in Goa, owning thousands of acres of fertile land and coconut plantations.

As per family tradition, Luis began his studies at the famous Rachol seminary, on the left bank of the Zauri river, where his subjects included Philosophy and Scholasticism. These allowed him to question and criticize the norms of men and society. At the age of 19, he joined the Lyceum school in Panaji and excelled in all his subjects. In 1900, his interest in science led him to enroll in a medical school, but he missed his first year examination due to typhoid. This was a turning point in not only his life but for the future of Goa.

Luis was passionate about reading and his family wealth allowed him to procure books and magazines from all over the world. By the early 20th century, Goa was just a sleepy backwater in a corner of the Portuguese empire, with little prospects for young men, who in turn migrated to places like Bombay for better future. It was through voracious reading, that Luis managed to keep abreast with happenings around the world. Influenced by great works of world literature and revolutionary ideas sweeping across the world, Luis dreamt of bringing change in the traditional and conservative Goan society.

As part of his belief that the Portuguese must go, Luis also studied the Konkani language and was a great proponent of replacing Portuguese with Konkani as the official language of Goa. In his essay ‘Why Konkani’(1914), he wrote:

‘It suffices for me that Konkani is our mother tongue and that no other will do for us as a mother tongue, however much we may learn them for culture's sake or for business' sake.’

In a society dominated by schools run by the church, Luis staunchly advocated the concept of Escola Neuter or a Neutral School, which would place education beyond all the limitations of faith and creed. Luis believed that this was the only way of establishing a liberal and tolerant society. He also wrote a number of books espousing his ideas of reshaping Goan society such as ‘The Comunidades and the Cult’ (1914), ‘The Castes’ (1915), ‘India and her Problems’ (1924), and ‘About an Idea’ (1928).

His writings also aimed at creating political consciousness which led to the establishment of the Congresso Provincial in 1916, in Goa. This was a local organization of prominent Goan citizens, formed to voice the issues of Goans to the Portuguese Government at Lisbon. Its purpose, composition and functioning were not very different from the early days of the Indian National Congress. In fact, it is quite interesting to note, how both the freedom movements in British India and Portuguese Goa evolved in parallel, following the same trajectory.

On 22nd January 1900, Luis teamed up with reputed Goan writer Professor Messias Gomes to launch Goa’s first newspaper ‘O Heraldo’. He was just 22 years old at the time. He wrote scathing columns attacking the Portuguese Government and the reactionary thinking of Hindu and Catholic intellectuals. A few years later, he also started writing columns for other publications and magazines such as O Nacionalista and O Commercio, building public opinion in favour of progressive ideas.

In 1911, Luis founded his own paper O Debate, which was published for ten years. In this, he wrote prolifically on topics ranging from caste and language to education and tourism. Luis was very keen on ushering in change and modernity in Goa’s conservative society.

One of the issues which he campaigned against extensively was the caste system that had crept into the Catholic Church in Goa. He wrote:

‘Deep down in the Goan soul painted with a varnish of Christianity, has remained encrusted with what is worst and nefarious in the caste system - repulsion. The divine grace conveyed through baptism was capable of eliminating the dressing style and the food habits but did not succeed in tempering the Goan soul in equality nor did it root out the caste prejudice which still held firm roots in the everyday social life.’

Just like Tilak urged Indians to fight for freedom against the British through his newspapers Kesari and Maratha, Luis too was fighting for a similar cause in Goa but against the Portuguese. Luis regularly contributed insightful and hard-hitting articles to the Marathi-Portuguese bilingual periodical Pracasha (The Light), propounding freedom from suppression and upholding the right to freedom of expression. From 1919 to 1921, he represented the district of Ilhas in the Government Council.

Luis Menezes Braganza’s most iconic movement came when the Portuguese dictator Antonio Salazar imposed the racist ‘Acto-Colonial’ in 1930. Before the act, the residents of Goa had equal rights as Portuguese nationals, but with this Act, they were made second class citizens. An added humiliation for the Goans was a reference in the Acto-Colonial that it was Portugal’s mission to ‘civilize the indigenous population’ of Goa.

As a member of the local assembly, Luis moved a strong resolution condemning this Act. There were few people in the Portuguese empire brave enough to take on Salazar, but Luis was one of them. In the assembly he thundered:

‘Portuguese India refuses to renounce the right given to all nations to attain the fullness of their personality until they are able to constitute units capable of guiding their own destinies, since this is an inalienable birthright’.

For this, he was widely hailed not only in Goa but across the Portuguese speaking world. Goan intellectuals granted him a title of ‘O Maior de Todos’ or ‘the Greatest of all’ while Indian press referred to him as the ‘Tilak of Goa’.

The push back from Lisbon was strong. In retaliation, the Portuguese government shut down all his publications in 1937. The Brazanga family believes that it was the stress and strain of these times, that contributed to Luis’s death due to a heart attack on 10th July 1938 in Chandor. He was just 60 years of age. Fearing an outbreak of nationalist protests, Portuguese troops were even stationed at his grave for a number of days.

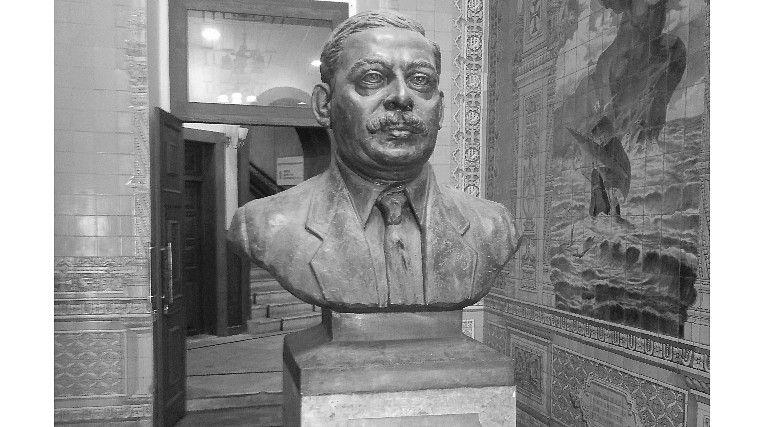

While it took 23 more years for Goa to be liberated from the Portuguese, Luis Braganza set the ball rolling with his tireless campaign to ensure that Goa marched into freedom. No wonder then that he is fondly remembered even today. After Goa was liberated in 1961, the noted Instituto Vasco da Gama, a prominent cultural institute in Goa was renamed to Institute Menezes Braganza in honour of his memory.

– ABOUT LIVE HISTORY INDIA