Mystery of Delhi's Iron Pillar

BOOKMARK

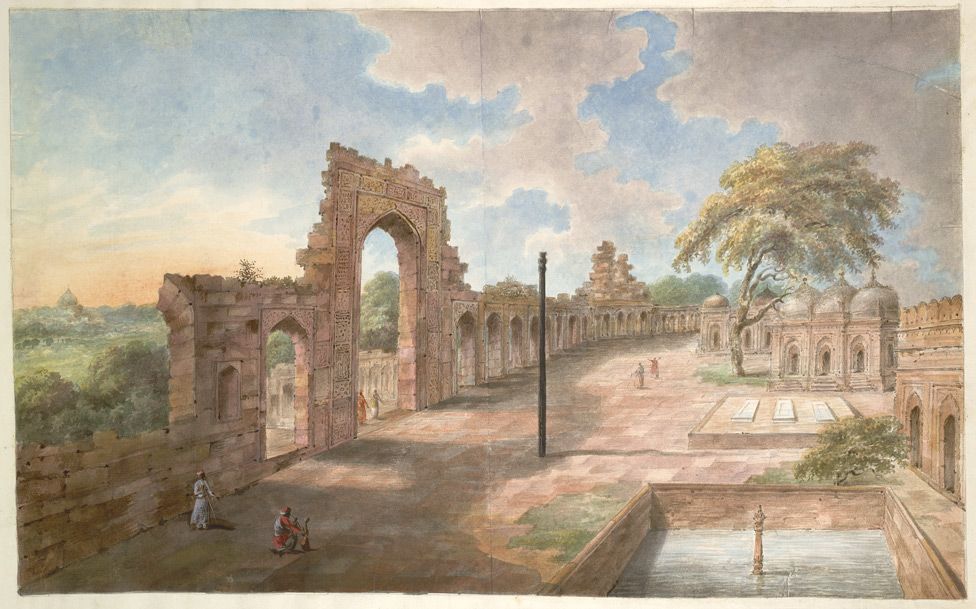

At first glance, it looks like an ordinary pillar, just another marker of an earlier time in Delhi’s layered history. All of 7.3 meters tall, it stands in the middle of an empty square in the Qutb Complex, which also houses the jaw-dropping Qutb Minar, in Mehrauli.

But take a closer look and you will see why this pillar is one of the most enigmatic structures in India. Made of iron, it should have turned into a pile of rust a long time ago, considering its age – it is 1,600 years old – and exposure to Delhi’s heat, dust, cold and rains.

But the Iron Pillar of Delhi is no alien mystery or futuristic hoax, as some would have us believe. It is a metallurgical wonder and a testament to the knowledge and skill of India’s ancient ironsmiths.

So, let’s tell you the Iron Pillar’s history, the story behind who built it, and the stories it tells.

The Mehrauli iron pillar stands in the middle of the remains of the oldest mosque in Northern India, the Quwwat ul Islam built by Qutubuddin Aibak (r. 1206 - 1210), the first Sultan of Delhi’s Slave Dynasty, in 1193 CE. In 1192 CE, Qutubuddin Aibak, then a general of Mohammed of Ghor (the Ghurid ruler of Afghanistan), defeated the Chauhan king of Delhi, Prithviraj Chauhan (r. circa 1177 – 1192), in the battle of Tarain. On the death of his overlord and patron, Mohammed of Ghor in 1206 CE, Aibak declared himself Sultan, thus setting the tone for 750 years of Islamic rule in Northern, Eastern, Western and Central India.

The Chauhan or Chahamana Dynasty of Delhi had risen to power after defeating the Tomars. The Tomar Dynasty, under its founder Anangapal, is said to have first settled the city of Delhi in 1052 CE, according to a small inscription etched on the iron pillar. The Chauhans conquered Delhi from them in 1152 CE under Vigraharaja IV, Prithviraj’s uncle, and ruled till they were defeated by Qutbuddin Aibak.

Origin Story

The Iron Pillar of Delhi weighs 6.5 tonnes, is 7.3 metres tall and has a slightly tapering shaft with an ornate abacus that was once topped by an animal capital. But what is of the greatest value for historians trying to piece together the story, are the Mehrauli Iron Pillar inscriptions, etched over a long period of time.

Inscribed on its shaft, on the side facing the mihrab arches of the ancient mosque, is a deeply incised inscription. This ancient inscription, in the Sanskrit language and Brahmi script, belongs palaeographically to the 4th century CE and is called ‘Gupta Brahmi’ after the Gupta Empire that ruled Northern and Central India from the 4th to the 7th century CE. It tells the pillar’s origin story.

According to the inscription, the pillar was erected by King Chandra and celebrates his victories in battle and was dedicated to the Hindu God Vishnu. There were two Gupta rulers named ‘Chandra’ but the one who is most definitely the one mentioned on this pillar is Chandragupta II, who ruled from 375 to 415 CE and extended the Gupta Empire till it extended to the Indus in the West, Bengal in the East, the Himalayas in the North and the Narmada River in the South.

But this was not the pillar’s original site. It is said to have been erected originally in the historically important city of Udayagiri in Vidisha (in present-day Madhya Pradesh), and according to popular myth was brought here by Sultan Iltutmish (r. 1211 – 1236) of the Slave Dynasty after he conquered Vidisha. He is said to have brought it to Delhi, his capital, as a trophy, much like the Ashokan columns brought to Delhi by the Tughlaq Sultans.

But there is another legend which says the pillar was brought to Delhi by the Tomar Rajput king Anangapal, who founded Delhi in the 11th century. It is said that he brought it here to adorn his capital city at Lal Kot, the ruins of which are visible in the vicinity, and the great Vishnu Temple that he built here. The Jain text, Pasanahachariyu (1132 CE) tells us that the pillar was so mighty and magnificent that “the weight of the pillar caused even the Lord of the Snakes to tremble”.

The pillar you see today is sadly incomplete. It originally had a capital atop as is attested by the deep dowel hole on the abacus. Since it was dedicated to Vishnu, it undoubtedly bore either a zoomorphic or anthropomorphic image of Garuda, the eagle mount of Vishnu. This was probably removed during the Sultanate period because the use of images went against the tenets of Islam.

Mehrauli Iron Pillar Inscription

The signage on a wall of the Quwwat ul Islam mosque where the pillar stands is the “translation and transcription of the inscription on the iron pillar”. It reads: “The residue of the king’s (Chandragupta II) effort – a burning splendour which utterly destroyed his enemies – leaves not the earth even now, just like the residual heat of a burned-out conflagration in a great forest. He, as if wearied, has abandoned this world, and resorted in actual form to the other world – a place won by the merit of his deeds – (and although) he has departed, he remains on earth through (the memory of his) fame.” The Mehrauli Iron Pillar inscription is an important piece of epigraphical evidence on the reign of the Gupta emperors.

According to yet another legend, this pillar was planted atop the head of Vasuki, the king of the Serpents (Nagas), and anyone who uprooted it would bring about the end of their dynasty. A later Tomar ruler did just that and the buried portion of the pillar is supposed to have been covered in blood, and soon, the Tomar Dynasty was defeated by the Chahamana (Chauhan) Dynasty. Interestingly, there is a small inscription by Anangapal on the pillar, dated to 1052 CE. According to Sir Alexander Cunningham, founder-director of the Archaeological Survey of India, the inscription reads, ‘Samvat Dihali 1109 Ang Pāl bahi’ or ‘In Samvat 1109 [1052 CE], Ang [Anang] Pāl peopled Dilli’.

Why the Pillar doesn’t Rust

The Iron Pillar of Delhi was made by a process known as ‘forge welding’ and the iron was not completely pure but included small portions of slag, a byproduct of the smelting process. Since ancient Indian ironsmiths did not use lime in the smelting process, the phosphorus in the ore was never removed. The impurities oxidised and the oxides interacted with the high concentration of phosphorus in the iron, to create a ‘passive protective film’ which retards corrosion, according to well-known IIT Kanpur metallurgist, Dr Ramamurthy Balasubramaniam. Thus, the ‘primitive’ process and the impurities that were not completely removed from the iron created an anti-corrosive layer which has ensured that the pillar survives in all its glory to this day!

The History of Pillars

There is a long history of pillars in India and the first of them were raised by the Mauryan Emperor Ashoka (r. 269 – 232 BCE). They were, in turn, reused by the Guptas and the Mughals (as seen on the Allahabad Pillar). We also have pillars used as ‘Garudadhvajas’ from Besnagar (in present-day Madhya Pradesh), where we have the pillar of an Indo-Greek envoy named Heliodorus. At Eran, also in Madhya Pradesh, we have a beautiful intact Garudadhvaja of the Gupta period dated to 485-485 CE.

Iron pillars are also known from other parts of India and there is a famous one at Dhar in Madhya Pradesh, and at Kodachadri in Karnataka. Similar victory columns are also known from Greece, Rome and Ethiopia, to name only a few other instances.

The raising of a pillar or lat (as called in Urdu) was a symbol of victory and so was the raising of a tower, as seen at sites like Chittor in Rajasthan and Jam and Ghor in Afghanistan. The beautiful Qutb Minar too is one such victory pillar. Thus, it is only fitting that the world’s tallest rubble-masonry structure and the world’s finest iron pillar stand in the same complex today.

Live History India is a first-of-its-kind digital platform aimed at helping you Rediscover the many facets and layers of India’s great history and cultural legacy. Our aim is to bring alive the many stories that make India and get our readers access to the best research and work being done on the subject. If you have any comments or suggestions or you want to reach out to us and be part of our journey across time and geography, do write to us at contactus@livehistoryindia.com