Swadeshi and Atma Nirbhar Bharat: Reinventing Nationalism

BOOKMARK

For those who think ‘Make in India’ and ‘Atma Nirbhar Bharat’ are new ideas created by a millennial government, it might surprise them to know of their deep roots in the 19th century. And, their deep practice in one form or another—feasible and flawed—for more than a hundred years. In a two-part series, here’s a deep dive into the journey of Swadeshi from its birth to its evolution, and its latest political arrival with brand new slogans.

“By June 1991, the balance of payments crisis had become overwhelmingly a crisis of confidence… A default on our payments, for the first time in our history, had become a serious possibility. It became necessary to take emergency action… The Government leaded 20 tonnes of gold out of its stock to the State Bank of India to enable it to sell the gold abroad with an option to repurchase it at the end of six months. Reserve Bank of India (was allowed) to ship 47 tonnes of gold to the Bank of England in July.” - Economic Survey 1991-92.

It is hard to find a more damning official indictment of the economic policies of independent India that came to a head in the spring and summer of 1991. There are many reasons the proud Indian Republic was literally brought to its knees that year: policies of recent governments, the first Gulf War, the fall of the Soviet Union and the resulting inability to juggle the macro-economic levers are the proximate causes.

Yet it was recognised that the real causes lay deeper — in the economic models that India had adopted since 1947, and even deeper, in the ideas that had led to their adoption. Chief among these were socialism as a way to redistribute wealth, the centrality of government in controlling economic activity and the achievement of ‘self-reliance’.

Despite being partly responsible for the crisis, the pursuit of ‘self-reliance’ is almost always left out of the chargesheet. In fact, eminent economists of the time argued that the crisis came about because we did not “strive harder for self-reliance”.

By 2021, though, ‘self-reliance’ was back on the centre-stage of India’s economic policy agenda: in the form of the ‘Make in India’ initiative in the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led Narendra Modi government’s first term that began in 2014 and ‘Atma Nirbhar Bharat’, or ‘self-reliant India’, in the second, after May 2019.

– The ideas of self-reliance, self-sufficiency and indigenisation form part of the overall narrative of ‘Swadeshi’, a word that literally means “of one’s own country” but is much more than that.

Underlying the economics is a challenge to social norms and values. More than being merely concerned with the purchase and production of Indian-made goods, ‘Swadeshi’ is an expression of economic nationalism within an idiom of resistance to outside powers.

Definition: From Patriotic to Practical

‘Swadeshi’ is a term that most people instinctively understand, but has meant different things to different people at different times. According to economic historian Tirthankar Roy, it is “nationalistic self-reliance”. His colleague Sumit Sarkar offers a more comprehensive and most accurate definition: “The sentiment — closely associated with many phases of Indian nationalism — that indigenous goods should be preferred by consumers even if they were more expensive than and inferior in quality to their imported substitutes, and that it was the patriotic duty of men with capital to pioneer such industries even though profits initially might be minimal of non-existent.” To Dattopant Baburao Thengadi, founder of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh-linked Swadeshi Jagran Manch, Swadeshi is “the practical manifestation of patriotism…a broad-based ideology embracing all departments of national life.”

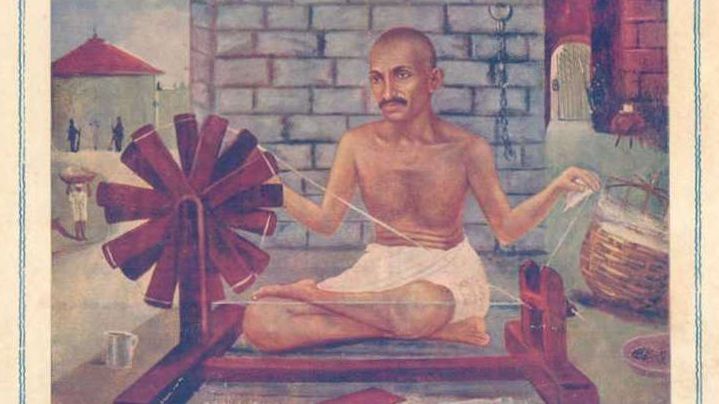

Gandhi offers perhaps the most extreme — and the intellectually the most honest — definition. In 1916, he described Swadeshi as “that spirit in us that which restricts us to the use and service of our immediate surroundings to the exclusion of the more remote… I must restrict myself to my ancestral religion. In the domain of politics, I should make use of the indigenous institutions… In that of economics, I should use only those things that are produced by my immediate neighbours and those industries by making them efficient and complete where they might be found wanting.” Almost a century later, Modi’s second administration compressed this into a very succinct “Vocal for Local”.

History: Swadeshi Before Gandhi

Although Gandhi is recognised as among the most prominent advocates of Swadeshi in the past century, it was with the Swadeshi Movement of Bengal (1903-1908) — over a decade before his arrival on the scene — that connected the idea to India’s struggle for freedom from British colonial rule. That movement, in turn, politically picked up the threads of Swadeshi from even earlier intellectual and social reaction in several parts of the subcontinent to the establishment of the British colonial state in the middle of the 19th century. Indeed, the earliest mention of the word ‘Swadeshi’ in the English language dates back to 1825, to the time when the East India Company’s rulers attempted social reforms in partnership with early Indian liberals like Raja Rammohun Roy.

As the historian Bipan Chandra notes, “The idea of, and the agitation for, swadeshi are, in reality nearly as old as the rising national consciousness itself.” In the family of ideas, therefore, swadeshi like liberalism and nationalism is a grandchild of the Enlightenment (and a distant but estranged cousin of Communism).

Evolution: Seven Phases of Swadeshi

Seven distinct, sometimes overlapping phases emerge while tracing the evolution of the Swadeshi idea over the past two centuries: the proto-Swadeshi phase (1820-1857); the early phase (1857-1890), when it entered social consciousness in several parts of the country; the emergent phase (1890-1903), during which it was embraced by organised political associations across the subcontinent; the phase of mass political struggle for independence from British rule (1903-1947); the policy phase (1947-1992) when it became a goal of the Indian Republic; the recession phase (1992-2016), when it was eclipsed by globalisation; and current populist reprise (2016 onwards), where it has again been declared a national priority.

Proto-Swadeshi (1820-1857)

The earliest consciousness of the need to protect indigenous goods and industries is likely to have emerged as part of the orthodox Hindu reaction to the social reforms (like the abolition of Sati) promoted by Christian missionaries and liberal reformers like Rammohun Roy in the early 19th century, after the East India Company government began to enshrine them as the law of the land.

The historian Christopher Bayly sees an “early intimation” of Swadeshi in an 1822 article in Chandrika Samachar, a conservative magazine, that complains that the foreign government had neither provided for training ayurvedic medical practitioners nor proper indigenous medical facilities.

In subsequent years, the advent of English education in 1835 and the proliferation of newspapers in Indian languages enabled individuals to acquire and spread political ideas and the developing national consciousness. Writing in a Marathi publication in Pune, the English-educated Gopal Hari Deshmukh in 1849 was among the first intellectuals to advocate the use of Indian products instead of imported ones. It was mostly in this manner that the development of economic grievances continued alongside political and cultural ones in the years leading up to the Uprising of 1857. Rebel manifestos of the period included accusations of how foreign imports had hurt native artisans.

Early Swadeshi (1857-1890)

Following the brutal upheavals of 1857 and the transfer of power to the British Crown, Swadeshi moved from idea to action. In Bengal, it found a champion in the form of the ‘National’ idea. Nabagopal Mitra who, inspired by Rajnarain Bose, set up the National Paper, National Store, National Gymnasium, National School, National Theatre and even a National Circus in quick succession in the late 1860s.

Significantly, he founded the ‘Hindu Mela’ in 1867 “to promote national feeling and to inculcate a spirit of self-help among Hindus by promoting Indian products”. Financed by the wealthy Tagore family, the annual festival ran up to 1880 and counted among its visitors the young Rabindranath Tagore and Narendranath Dutta (later known as Swami Vivekananda), both of whom made important contributions to the Swadeshi discourse.

In the 1870s in Pune, inspired by Mahadev Govind Ranade’s lectures, Ganesh Vasudeo Joshi started shops to sell Swadeshi goods, in addition to spinning yarn every day for his own clothing, a practice that Gandhi made famous four decades later. The decade saw the sprouting of Swadeshi stores in many cities across the country, with railways, the telegraph and newspapers accelerating the spread of the idea. The Government’s decision to abolish import duties on British cotton goods in 1882 added more fuel to the growing Swadeshi fire, bringing mill owners into the fold.

– One political mobilisation that featured Swadeshi, boycotts and non-cooperation during this period was in Punjab in the 1860s, where the 12th Namdhari Guru, Ram Singh enjoined his followers to abjure everything British as he envisioned “driving the English out of Hindustan”.

For the most part, though, the Swadeshi cause did not have an overt political instrumentality.

Emergent Political Phase (1890-1903)

By the late 1880s, political associations began to take an interest in the Swadeshi agenda. It first entered the deliberations of the Indian National Congress in 1891, but it was only in 1896 that it became a national cause, after the Government imposed excise duties on manufactured Indian cloth.

In the Bombay Presidency, Bal Gangadhar Tilak organised boycotts and public burnings of foreign cloth, amid widespread public support across the country. In the event, the protests were insufficient to persuade the Government to lift the excise duties, which remained in place till 1925. It did, however, become a regular part of the Congress’s agenda in the 1890s with exhortations, appeals and actions albeit without a formal endorsement.

By this time, Swadeshi had already become a social proxy against what many saw as political ‘mendicancy’. As the temperature of nationalist sentiment outstripped the Congress’s appetite for confrontation with the Government, ‘atmasakti’ or ‘self-reliance’ and ‘constructive work’ became the new slogans—starting Swadeshi enterprises and stores, trying to organise education on autonomous and indigenous lines, and emphasising the need for concrete work at the village level. Such efforts at self-help, together with the use of the vernacular and utilisation of traditional popular customs and institutions (like the ‘mela’ or fair), were felt to be the best methods for drawing the masses into the national movement.

– Most of the Indian capital in the mid-19th century was invested in land, agriculture, trade and arbitrage.

The global economic changes of the time — the industrial revolution, abolition of slavery, the American Civil War and the indigo and opium trade — did have an influence on changing the pattern of the deployment of Indian capital. The earliest Indian investments in industry were made in the mid-1860s. By the 1890s, nudged by Swadeshi, the more entrepreneurial Indian capitalists started investing in cotton mills and consumer goods like soaps, locks and pharmaceuticals, as also in ventures in shipping and transportation.

Read the second part of this essay here

– ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Nitin Pai is co-founder and director of the Takshashila Institution, an independent centre for research and education in public policy.

This article is part of our special series the 'Making of Modern India' through which we are focussing on the period between 1900-2000. This century saw the birth and transformation of India. This series aims to chronicle India's exciting journey and is a special feature brought to you by LHI Foundation.