Many Voices, One India

It was a diehard Gandhian who tested the will of Jawaharlal Nehru soon after he was sworn in as the first elected Prime Minister on 13th May 1952. Just five months later, Potti Sriramulu began a fast-unto-death in Madras. He was demanding the creation of a separate state of Andhra for the Telugu-speaking people of the Tamil-dominated Madras Presidency.

Fasting was a weapon Gandhi had used successfully on numerous occasions against the British Raj. Now Sriramulu was using it against free India’s government. Earlier, in 1946, he had undertaken a fast for the entry of “low castes and untouchables” into temples in the Madras Province but gave it up on Gandhi’s advice.

Six years later, Gandhi was not around. But Sriramulu was no ordinary Gandhian. He was among the 79 disciples who had accompanied Gandhi on his historic Dandi March to break the Salt Act. Gandhi respected Sriramulu’s commitment although he thought he was a little “eccentric”.

Sriramulu’s indefinite fast caught the nation’s attention as his health deteriorated. Still, Nehru ignored the groundswell of support among the Telugu-speaking people for Sriramulu’s cause. He spoke strongly against the creation of Andhra Pradesh and other new states on the basis of language, warning that conceding the demand would open a Pandora’s Box. It would set off a chain reaction of demands for the creation of linguistic states, posing a threat to the unity of the country.

By 1952, India had overcome most of the existential challenges it had faced after the nation attained freedom. The post-Partition communal conflagration had subsided, refugees were being settled, the princely states had merged with the Union, a communist rebellion had been put down in Hyderabad State, and Pakistani raiders had been pushed back in Jammu & Kashmir.

India had surprised the world, a very sceptical world, by conducting a free and fair election based on universal adult franchise, to begin its democratic journey. She proved the Cassandras of doom wrong. The Western world still had a jaundiced view of India as many writers felt the fledgling Indian democracy wouldn’t last long and India would break into many independent nations.

Selig H Harrison was a prominent American journalist and author based in Delhi in the 1950s and 1960s. In his book India: The Most Dangerous Decades (1960), he wrote, “The odds are almost wholly against the survival of freedom and the issue is whether any Indian state can survive at all.” There were myriad such voices of doom and gloom.

Nehru and the other Congress leaders were conscious of the lurking dangers of communal, parochial, fissiparous and chauvinist tendencies that could raise their ugly heads and endanger the newly forged unity of the country. Language was one of them as it had the emotional appeal to either unify or divide the people.

It was an issue that was still not settled as the debate surrounding the status of Hindi and the demand for the formation of linguistic states continued. The Constituent Assembly debated the matter but the issue was hanging fire.

So when Sriramulu’s fast progressed in the house of one Sambamurthy in the Mylapore locality of Madras, from days to weeks, Nehru ignored it at first and later spoke about the dangerous implications of forming linguistic states. His concern was that India had already been divided along religious lines, it couldn’t afford to risk any further divisions by stoking emotions – whether language or anything else.

Little did Nehru realise that the Gandhian would give up his life for his convictions. On 15th December, on the 58th day of his fast, Sriramulu died. People in 11 Telugu-dominated districts of Madras State took to streets, and riots broke out, forcing the police to open fire. In many places, protesters were killed. Three days later, on 18th December, the government agreed to the creation of Andhra Pradesh.

Andhra Opens The Floodgates

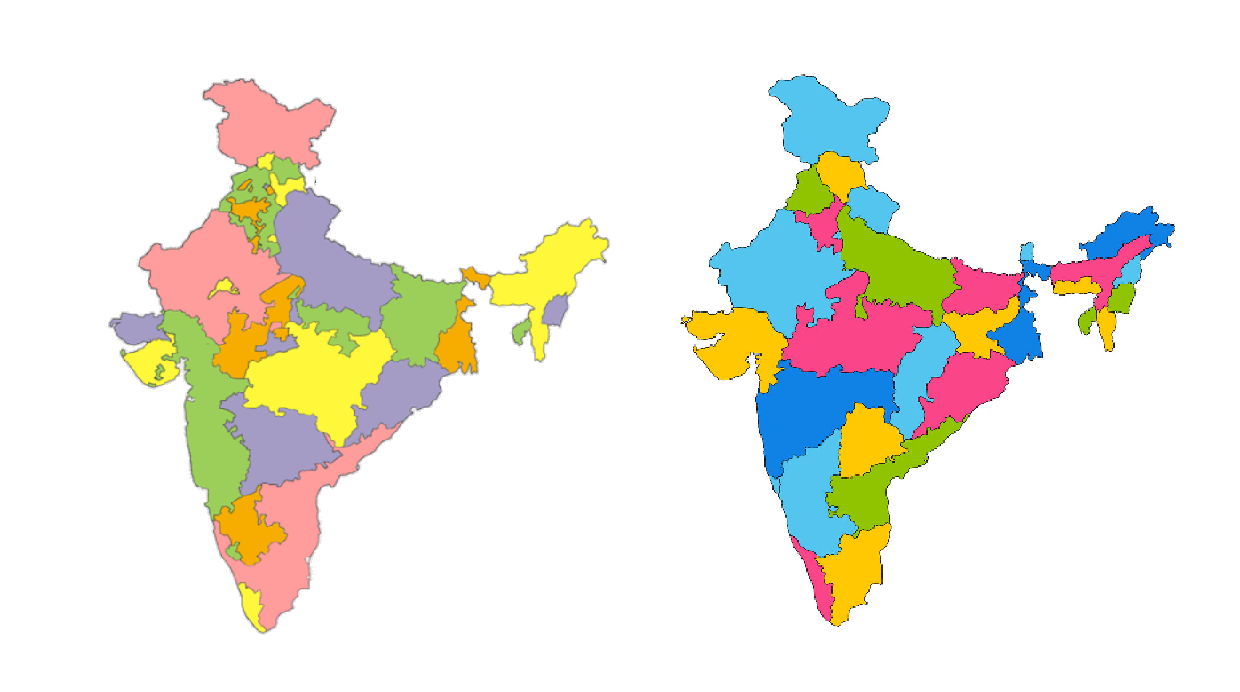

As Nehru had predicted, the government’s decision did open a Pandora’s Box. It set off a process that continued well into the 1960s. Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Kerala, Maharashtra and Gujarat were born as linguistic states by reorganising the boundaries of the old provinces that had been haphazardly drawn by the British, mainly for administrative purposes.

India is a land of 22 major languages, each with its distinct script, history, culture and rich literature, besides the 1,000 dialects in the country. Voices for the creation of linguistic states are still heard occasionally but they are not loud. After the trifurcation of Punjab, the formation of new states has taken place mainly on administrative, geographical and ethnic grounds, not on a linguistic basis.

– The genie of the linguistic division of states was ironically let out of the bottle by the Congress. At its 1916 and 1917 sessions, the Congress promised the formation of new linguistic provinces after Independence.

In 1921, when Gandhi emerged as the foremost leader of the freedom movement, the Congress reorganised its provincial branches on a linguistic basis. In 1928, a committee headed by Motilal Nehru recommended the reorganisation of provinces on linguistic lines.

At the 1937 session in Calcutta, the Congress went a step further to accept the principle of creation of states for Andhra and Karnataka. A year later, at the Wardha session in 1938, the idea of the formation of Kerala was approved. In 1936, the movement for creation of a separate state for Oriya speakers succeeded. The British carved out Orissa (now Odisha) as a state from parts of Bengal and Bihar.

Gandhi was the most vocal proponent of linguistic division from 1921. In January 1948, a few days before he was assassinated, he said, “The redistribution of provinces on a linguistic basis was necessary if provincial languages were to grow to their full height.” On another occasion, he said, “We should hurry up with reorganisation of linguistic provinces.”

Nehru’s stand was more broad-based. He emphasised the diversity, rich heritage and cultural history of provincial languages and called for their growth. It is pertinent to point out that the Congress manifesto of the 1945-46 elections promised the reorganisation of states on linguistic lines.

Dr B R Ambedkar didn’t outrightly reject the idea of linguistic states but he felt that in a state dominated by one major language, the minority speakers of the other languages could suffer discrimination.

In the wake of the Partition riots, Nehru prevaricated. He felt the issue of language had the potential to divide the people and, therefore, sought to make economic development and political unity the focal point of nation-building. On 27th November 1947, Nehru sent out a clear message against linguistic states by stating, “First things must come first and the first thing is the security and stability of India.”

The Constituent Assembly deliberated the issue but failed to reach a consensus. A Linguistic Provinces Commission was appointed to examine the matter. It was headed by S K Dar, retired judge of the Allahabad High Court, and included two other members. The Dar Commission’s recommendations were against the formation of states based “exclusively or even mainly on linguistic basis”. It expressed apprehensions that linguistic states would create a minority problem within the states.

The Dar Commission’s recommendation didn’t find favour with the Constituent Assembly. At the 1948 session of the Congress in Jaipur, a three-member committee was set up to further examine the question. The members of the committee were Nehru, Sardar Patel and Pattabhi Sitaramayya, the Congress President. It was known as the ‘JVP (Jawaharlal, Vallabhbhai, Pattabhi) Committee’.

The JVP committee advised against the formation of linguistic states. Nehru justified the party’s volte face, stating that when the Congress had approved the principle of linguistic states, it had not deliberated its practical implications. Yet, the committee said, a linguistic state could be formed if there was an overwhelming demand for it and if the minority speakers in the state were agreeable, without jeopardising the political and economic stability of the country.

The JVP Committee approved the creation of Andhra Pradesh, on condition that the city of Madras wouldn’t go to the Telugu-speaking state as it was a Tamil-majority area. Even though the Telugu speakers were adamant on getting Madras, they had to eventually forfeit the city.

Reorganisation Is Inevitable

Ever since the formation of Andhra Pradesh in 1953, the demand for other linguistic states grew louder and the government set up the States Reorganisation Commission (SRC) with Justice S Fazl Ali, H N Kunzru and K M Panikkar as its members. The SRC submitted its report in 1955. Based on its recommendations, Parliament enacted the States Reorganisation Act in 1956, implementing most of the SRC’s recommendations. The SRC Act provided for 14 states and six Union territories.

Based on the SRC’s recommendations, the boundaries of Andhra, Madras, Mysore and Kerala were redrawn. Parts of the old Hyderabad state merged with Maharashtra, Mysore and Madhya Pradesh. Madras and Mysore were later renamed as Tamil Nadu and Karnataka. The formation of the new states of Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Karnataka, on the basis of well-defined language zones, was uncomplicated.

Likewise, the SRC’s task in North India was easy, where the Hindi-speaking states of Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Bihar and Rajasthan presented no difficulties in reorganisation. Gargantuan in size, these states had no major linguistic fault lines but they were unwieldy from an administrative point of view. Some of the states did have ethnic and cultural fault lines. For instance, parts of Bihar and Madhya Pradesh had huge areas of large tribal populations with their distinct culture, languages and way of life. The SRC had completely ignored the tribal question.

In 2000, the Atal Behari Vajpayee government announced the formation of two new states, Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh, with substantial tribal populations, and a third mountainous state of Uttarakhand.

The Bombay Dilemma

One of the most vexed issues that confronted the government after the formation of Andhra and with the intensification of demands for new linguistic states was the status of Bombay. The city was a potpourri of residents who spoke Marathi, Gujarati, Sindhi, Urdu and Hindi, Konkani and many other languages.

The city was a hub of industry and business. While delineating the boundaries of Maharashtra and Gujarat along linguistic lines wasn’t a problem, the city of Bombay remained a bone of contention. Both Marathi and Gujarati speakers laid claim to Bombay after the SRC report came out.

– A group of industrialists including prominent business magnates such as J R D Tata were part of the Bombay Citizens Committee that campaigned to keep the city out of Maharashtra.

The committee was mainly financed by Gujarati businessmen who were apprehensive that Maharashtrians as the largest demographic group would dominate Bombay.

The SRC recommended Bombay be given the status of the capital of a bilingual state. However, the Samyukta Maharashtra Parishad, which was spearheading the movement for a state for Marathi speakers, opposed the SRC’s recommendation. They insisted that the status of Bombay was non-negotiable. Soon the movement took a violent turn, with protesters burning and looting properties and battling the police in the streets. As many as 80 protesters were killed in police firing in a week of street protests, in January 1956.

Rattled by the violence, the government in June 1956 decided to divide the then Bombay State into the two linguistic states of Maharashtra and Gujarat, with Bombay city becoming a centrally-administered state. The Maharashtrians opposed it. In July, Nehru again decided on the formation of a bilingual greater Bombay, which was opposed both by the Samyukta Maharashtra Samiti and the Maha Gujarat Parishad.

More political turmoil followed as C D Deshmukh, Union Minister of Finance – who was earlier the first Indian Governor of the Reserve bank of India – resigned from the Cabinet. Violent protests over the status of Bombay spread to Ahmedabad and other areas of Gujarat, where more than a dozen people were killed in police firing.

On 1st November 1956, a new bilingual state of Bombay was formed. And in a political move, the Gujarati-speaking Chief Minister of Bombay State, Morarji Desai, was replaced by the Marathi-speaking Y B Chavan.

Four years later, on 1st May 1960, the bilingual Bombay State was split into a majority Marathi-speaking state of Maharashtra and a Gujarati-speaking state of Gujarat.

During the first decade after Independence – from December 1952 when Potti Sriramulu died, till 1960 – the government grappled with a rising tide of emotion sparked by linguistic nationalism. Some may even call it ‘lingual fanaticism’. Professor Suniti Kumar Chatterjee, one of the greatest linguists of India, was not sure the country would survive this ‘lingual nationalism’. He felt the speakers of major non-Hindi languages with their distinct lingual identities and culture would not live for long with Hindi heartland states.

Nothing of the sort happened and the fears over linguistic states fuelling secessionist tendencies were belied.

The redrawing of India’s map on the basis of language strengthened the federal structure of the Union. Linguistic states satisfied the cultural yearnings of the people. It gave them a certain cultural autonomy and identity.

The Gandhian Potti Sriramulu’s death-by-fasting had altered the map of India.

This article is part of our special series the ‘Making of Modern India’ through which we are focussing on the period between 1900-2000. This century saw the birth and transformation of India. This series aims to chronicle India’s exciting journey and is a special feature brought to you by LHI Foundation.