Kerala Caste Politics: Renaissance vs Hindu Revivalism

Even with more than a century of battles and reforms, caste and conservative Hindu revivalism remain crucial elements in society and in Kerala’s often-incendiary politics. Indeed, an actor-director associated with a new political entity in the fray for the Assembly elections in Kerala on 6th April 2021, even raised a sarcastic question: “What is Kerala navoththanam (renaissance)? Is it something like Chyavanprash?”

The dismissive allusion is similar to efforts that seek to squander the steady gains of the social awakening of the late 19th and early 20th centuries that socially transformed the British-administered region of Malabar and the princely states of Kochi and Travancore that largely make up present-day Kerala.

Historians are divided over whether the peripatetic Swami Vivekananda called Kerala a “madhouse” or a “lunatic asylum” during his tour in 1892 of the three regions that now make up Kerala, before he headed towards Kanyakumari.

Either way, it is clear that he had great contempt for the way people of the upper castes in the region treated the others.

The collision of castes continues, and debates around the socio-political and cultural renaissance of the past two centuries in Kerala crop up often, with a section trying to undo the gains that the majority of its people acquired through a prolonged battle to replace regressive traditions with egalitarian laws.

True, the region wasn’t called Kerala then. Before its formation on linguistic lines in 1956, it was a collection of three zones: Malabar in the north (which fell under the British presidency), and Kochi and Travancore, which were princely states. Some Tamil-speaking areas later became part of the neighbouring Tamil Nadu and Kannada-speaking ones of Karnataka, but more or less, current Kerala is broadly a union of these three regions.

Kerala’s Renaissance is not any ayurvedic tonic or preparation, and contrary to those who denigrate it, it is what made Kerala a geographic entity with social indices at par with those of Nordic countries. Navoththanam, or renaissance, was also a constellation of disparate reformist movements that started in the 19th century and gathered greater momentum in the first half of the 20th. It continues to the present day, despite efforts to reverse its rewards for the majority.

Why is that even some of its biggest beneficiaries, which includes a large chunk of the state’s communities, despise navoththanam even though it transformed Kerala from the “madhouse” it was to a saner place?

Let’s return to Swami Vivekananda’s visit to Kerala. It was preceded by a meeting in Bangalore some time earlier with Dr Palpu, a highly qualified doctor from Travancore who was disallowed a position in the health department of the state because he belonged to a lower caste. He, however, was hired by Chamarajendra Wadiyar X, the Maharaja of Mysore of the time. Palpu, after narrating the injustices perpetrated over caste in his state, sought advice from Swami Vivekananda on how to lead the struggle to emancipate members of his community, the numerically preponderant Ezhavas, from their marginalised existence.[1]

This was followed by the drafting of the ‘Malayali Memorial’ which was submitted to the Maharaja of Travancore to protest “undue favours given to Tamil Brahmins in official appointments”. According to the website of the Kottayam Public Library, where it was drafted, “It (Malayali Memorial) was signed by 10,037 persons and presented to the Maharaja on January 1st 1891, demanding immediate corrective action. Leaders of the discussions and drafting were K P Sankara Menon, G P Pillai, Dr Palpu and Advocate Nidhiri.”

During his Kerala visit a year later in 1892, Vivekananda saw for himself the ugly face of the prevailing caste rules and found it worse than he had imagined them to be. He believed that of all places he had been in the India of the time, caste discrimination in erstwhile Kerala was the most dreadful and appalling.

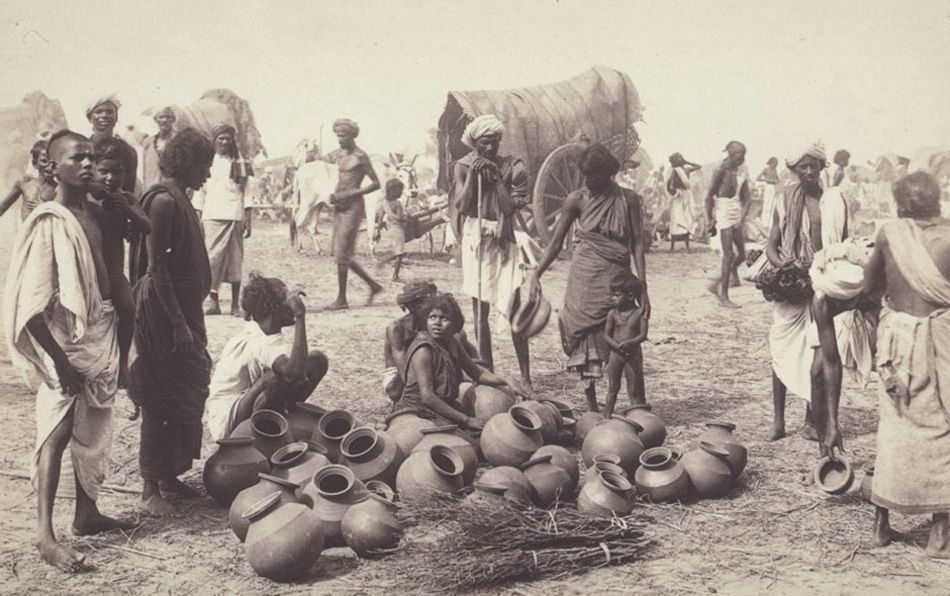

In fact, efforts had begun to set things right much earlier, but progress had been slow. The general name for that gradual but consistent effort is navoththanam. The missionaries of the London Missionary Society (LMS) deserve credit for making initial and dramatic efforts to break the rigidity of caste and offer lower castes an opportunity to break free of the shackles of caste hierarchy. The concept of ‘unseeables’ (those who cannot even be seen by upper castes) was so deep-rooted in Travancore that any of them seen by an upper-caste person was punished, even sentenced to death. Those who converted to Christianity had the freedom that was denied to former untouchables and unseeables.

While lower castes still confined to the Hindu system had to struggle to avoid being seen or touched by upper castes and others depending on their status—never mind that their women were considered fair game for sexual assault, sex slavery and rape by the upper castes—converted Christians felt empowered, thanks to the British rule that facilitated the activities of LMS to flout many kinds of caste rules.

Samuel Mateer, whose works are still the most referred texts to understand the Kerala society of the 19th century, writes in his Native Life in Travancore, “…Another distinctive feature of the mission arising, in the providence of God, in large measure, from the oppressions practised on the lower castes, and from the beneficent dominance of the British, was the coming over of the people in masses, influenced no doubt at first, and to some extent still, by inferior and selfish considerations; not of course, for temporal support, but for sympathy, protection and aid in their distresses… and they witnessed Christianity elevating the first and each successive generation of converts in education, social status and personal worth.” LMS and Protestant affiliates were also destined to play a crucial role in giving the oppressed classes access to modern education as well as health care.[2]

It was not just the British Protestants who began to change the rules of engagement in Kerala. Thanks to the winds of change sweeping the state due to the arrival of European values of renaissance, just as it did in other parts, Catholic priest Kuriakose Elias Chavara set up a school in Mannanam in the southern district of Kottayam in 1846 where he admitted students from the ‘untouchable’ castes. He didn’t stop at that: he also provided them a Sanskrit education—hitherto the domain of the upper castes. He offered mid-day meals to the students, which inspired authorities in Travancore to later adopt the practice in all government schools.

It must have been such pioneering efforts of people of other religions to uplift lower castes that later made the noted reformer Sree Narayana Guru say around the time of World War I that it was the British who gave him sanyasam (sagehood). His reasoning was that if he were born in a Ram Rajya or something similar, he would have met the fate of the mythical shudra ascetic Sambuka, who, for the ‘crime’ of seeking sagehood through penance, was beheaded by Ram himself.

Narayana Guru had illustrious predecessors not only among people of other religions, but from so-called Hindus as well. In fact, conversions to Islam also happened during the period, with lower castes seeing rays of hope outside the Hindu religious hierarchy. Unlike in other parts of India, Islam came to Kerala centuries earlier, not through invaders but via traders, along with other religions like Judaism and Christianity. All these groups often mixed with the local population. This is a key difference overlooked by certain groups whose anti-Muslim ideas originated based on the northern and western Indian interpretations of Mughal rule and loot by invaders.

Filippo Osella and Caroline Osella note in their work Islamism and Social Reform in Kerala, South India: “From a Kerala perspective, Islamic reformism is not at all peculiar. The reformist programmes articulated from the end of the 19th century onwards by various Hindu and Christian communities have much in common with similar processes taking place amongst Kerala Muslims; all are responding to and reflecting upon similar historical contingencies and also reacting to each other.”

Escaping caste oppression—in effect, tradition—was the craving of the time.

The Hindu reformers that preceded the coming of Narayana Guru, whose contribution is counted as foremost, were Ayya Vaikundar (known to be a mystic who was scathing in his criticism of both the Travancore and the British rulers; he was jailed briefly for his comments against them); Thycaud Ayya; women who led the maaru marakkal samaram (agitation to cover their breasts); Chattambi Swamikal; and others.

Chattambi Swamikal was a contemporary of Narayana Guru. So was Ayyankali, who is sometimes referred to as ‘Kerala’s Spartacus’, who launched an agitation against the restrictive and regressive laws on Dalits, which included a demeaning dress code (women had to wear a necklace made of stones and men could not grow their beards) and a ban on entry on certain roads.

A great revolutionary, between 1891 and 1893, he rode decorated bullock carts (villu vandi) through public roads in southern Travancore, defying a ban on Dalits to use such roads. His protest with carts peaked with a confrontation in Balaramapuram, Thiruvananthapuram, in 1893, when he braved caste supremacists and their attendant toughs. He also started schools and was instrumental in encouraging Dalit girls to pursue studies.

There are numerous other names from among the disciples of people mentioned here and others who were self-made social reformers in the 19th and the 20th centuries, and the thrust of their mission was to break existing traditions, not to retain them.

The legacy of the early reformers was carried forward by Congressmen from various communities: social leaders from Brahmins to Dalits. And then came the communists who attracted idealists to join them. A two-word summation of what they all did is: break traditions. It happened as envisaged by Renaissance poet and Sree Narayana Guru’s disciple Kumaran Asan: Mattuvin chattangale! Swayamallenkil mattum, athukalee ningalethan! (Change the rules! If you don’t, those rules will lead to your big fall).

That is exactly what satyagrahis who fought for the entry of lower castes to the Mahadeva temple in Vaikom, by the backwaters between Kochi and Alappuzha, did in 1924-25, although the fruits of their efforts came later. Mohandas Gandhi himself landed in Vaikom to plead with the Namboodiris of Indanthuruthu mana, custodians of the temple. Along with him were C Rajagopalachari, Mannathu Padmanabhan, another noted social reformer, and others.

The Brahmin priests made Gandhi sit outside their home because he was a Vaishya by varna. The Namboodiris of Indanthuruthu mana (the dwelling places of the Kerala Brahmins were called mana) didn’t relent, but argued that Kerala was granted to them by Lord Parashurama (an avatar of Lord Vishnu) by throwing his axe into the ocean. Call it irony: that particular mana is currently the office of a toddy tappers’ trade union.

Questioning traditions and existing laws are quintessential to any renaissance. That is what Kerala saw in Nivarthana samaram (abstention agitation) in 1933. This followed the Legislative Reforms Act 1932 brought in by Sri Chithira Thirunal Balarama Varma, the Maharaja of Travancore, which made land ownership the primary criterion for membership in the Legislature and public services. The numerically strong Ezhavas—since classified as ‘Other Backward Caste’ by the Government of India—Christians and Muslims came together and rose in revolt. C Kesavan, who later became the chief minister of the short-lived Travancore–Cochin (Thiru–Kochi) state, was one of the most prominent faces of this movement whose impact was profound: it ended the monopoly of those who enjoyed power because of property ownership.

Similar things happened in other parts of the state, too. Spearheaded by K Kelappan, the Guruvayur temple entry satyagraha of 1932 also demanded entry for ‘untouchables’ into this famous centre for worship. Volunteers included A K Gopalan and P Krishna Pillai, who would later become communist stalwarts; Nair leader Mannathu Padmanabhan and others. It was a failure, but four years later, Travancore’s Maharaja Chithira Thirunal Balarama Varma issued the temple entry proclamation which reversed the ban on the entry of the ‘avrana’—a huge departure from tradition.

From peasant resistance in Malabar in the north to greater representation for those who had never been in power in Travancore, the decades that followed saw the greatest social churn Vivekananda’s “lunatic asylum” had never seen, turning it quickly into a place where social justice grew firm roots. Naturally, there was resistance. One occasion when there were efforts to set the clock backwards was the political decision to dismiss the communist government of EMS Namboodiripad in 1959, which had begun to work towards land-ownership and school reforms soon after coming to power, making land and education accessible to all and not just a few. In hindsight, Congress leaders publicly expressed regret over the toppling of an elected government through a strike. Most of them laid the blame on Indira Gandhi, daughter of then Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, for colluding with ‘caste monsters’ to remove Kerala’s first state government.

But Brahminical patriarchy resurfaced in 2018, when various forces came together against the 28th September verdict of the Supreme Court that lifted an earlier ban on the entry of young women of menstruating age into the temple at Sabarimala where the deity (Ayyappa) is considered a naishtika brahmachari (eternal celibate). The ruling CPM in the state went all out to ensure that the court’s verdict was enforced. The government was shocked at the response: thousands of women joined the ranks of protesters. How did it happen?

It could be because the Left and secular parties for at least a few decades until then had vacated their role as a reformist force over political expediency, letting conservatism gain a foothold, step by step. “What is navoththanam?” is a question that stems from an indifference or unfamiliarity with history. It is tragic because it provides space to such misplaced nostalgia and misreading of Kerala’s cruel and unjust past.

In 1970s Kerala, celebrated author and chronicler of Kerala’s history Robin Jeffrey sought an answer to a seminal question: How did Kerala's reputation for assertiveness grow out of a society that was once noted for its ordered rigidity? (Politics, Women and Well-Being: How Kerala Became a Model). He was searching for answers to the emphatic shift to a place where people won back dignity. But the Sabarimala experience of 2018 showed that conformism breeds on itself and that memory—of a slavish and hideous past in this case—can be a fickle thing.

Meanwhile, there are also plans to portray Narayana Guru as a Hindu revivalist although the late Guru had consecrated a mirror in place of a deity and had said that there are enough temples and that what people now needed were more schools. In his book, Writing the First Person, Professor Udaya Kumar had highlighted the complex nature of Guru’s work and how his legacy could be construed: “Sree Narayana’s interventions towards altering practices of worship have generally been seen as efforts to civilize Ezhava rituals and bring them in tune with upper-caste Hindu methods.” He also writes about the other side of the argument that they were also seen as “acts of appropriation by which dominant Brahminical practices are made to serve the ends of new social groups.”

To attribute revivalism to Sree Narayana Guru, who had dismissed the chaturvarna system as no different from the caste system of his day and had fought to replace it, is plain opportunism and a gross misreading of his life and times—as is denigration of the benefits of Kerala’s renaissance.

So too is a draft legislation publicized by the Congress party ahead of the Assembly elections which suggests that those who violate the customs and traditions at Sabarimala will face arrest and imprisonment up to two years. It is a capitulation of all values that Gandhi and Kerala’s Renaissance stood for.

[1] Dr Palpu: The Pioneer Ezhava Social Reformer of Kerala, 1863-1950 by T P Sankarankutty Nair; Proceedings of the Indian History Congress; Vol. 40, 1979

[2] The History of the London Missionary Society in Travancore, 1806-1908; By RN Yesudas; Kerala Historical Society, 1980

– ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Ullekh NP is Executive Editor of OPEN magazine, and the author of three books, Kannur: Inside India's Bloodiest Revenge Politics, The Untold Vajpayee: Politician and Paradox and War Room: The People, Tactics and Technology Behind Narendra Modi's 2014 Win.